Hey, thanks for the great discussion in various places about Friday’s post talking about how to identify and describe creeps. Several really important points were brought up, and I want to highlight them this morning.

First, creepiness and boundary-pushing aren’t limited to the world of dating or other potentially romantic or intimate relationships. Creeps appear among all types and affecting every kind of relationship. Think about that person who hangs out with your social group but who nobody really likes, or the family friend who skeeved you out as a kid, for example. Young, old, male, female – there is no standard look for creepiness. The only defining characteristic is that they keep persistently acting in ways that make folks uncomfortable, ways that do not change in significant ways even if they are gently told or shown that how they’re behaving is unacceptable. Creeping isn’t always intimately physical and it isn’t always about inappropriate gifts or gestures. It can be as seemingly harmless as disrespecting another’s personal space on a regular basis, or continually and pushily asking clearly unwelcome questions. They may never do anything overtly wrong, but if they do, nobody is truly surprised.

Part of the problem with learning to tell if someone is nudging up against your boundaries is that it can be difficult to understand how to draw and enforce those lines in the first place. Boundaries are statements of what you do not want to allow someone to do to you. In regular life, we may have different boundaries for different people and classes of people, and we may bend them as part of our relationships with them. That’s all fine and good when it’s a voluntary negotiation on both sides, where there’s give and take and your decision to allow a person to interact with you in a certain way results from clear, two-way communication. It’s a lot more complicated when there’s a power imbalance, or when societal norms add pressure for you to change your boundary or allow it to be broken, even ever so slightly. And as several parents pointed out, one of the toughest times this happens is with young children who are asked to hug relatives and other adults even when they don’t want to. If, as children, we are forced past as personal of a boundary as who is allowed skin-to-skin touch with us, how can we know what boundaries are acceptable to have and to firmly defend? Realizing that, how can we change how we understand boundary creation and enforcement?

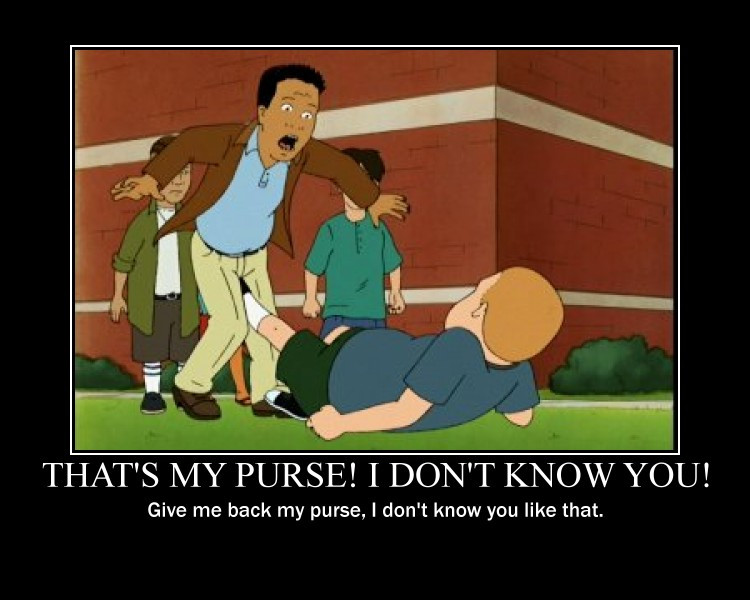

I’m not saying that it’s important for you to have rigid boundaries and that any brush against them sparks off a Bobby Hill-like reaction like this meme, but you do need to be able to clearly communicate and consistently defend each boundary you have between yourself and another person. It’s difficult and unfair to expect people to respect a limit with you if they don’t know what it is. Much like I said last week, you are responsible for saying yes when you mean yes and more vitally, no when you mean no. Using the words is only part of the equation too, because it’s also on you to ensure that your tone and body language are also saying yes when you mean yes and no when you mean no. Unfortunately, we live in a world where people often feel that it’s mean to say no, or that they’ll be shamed if they say yes, even if that’s what they really want. Contributing to that confusion helps nobody, and can create awkward situations (and more difficult to legally justify defenses) when someone acts in a way that reflects what they think you meant because you sent mixed signals. It’s not that you are responsible for another person’s actions when they misinterpret you, but why make it harder for everyone by not being crystal clear?

It’s not necessary to be rude in the process either, at least not in the very beginning. You can be polite and kind when you tell somebody that no, you would not like a drink of any kind from them, or that no, you’re not up for hugging them hello or goodbye. You don’t have to also say that you wouldn’t want that drink or hug if they were the last person on earth, and by the way they smell and their mother was a hamster. Courteous words and polite language may be completely appropriate to the setting you’re in and the person you are or would like to be. Making a scene is not required, at least not at first. You might have to, if the point is being missed, whether deliberately or not, and that’s okay too. Rudeness might also be completely appropriate to the context. The trick is to learn how best to navigate when you should be one over the other, and how best to do so clearly, so that you can avoid escalating situations that don’t need to be escalated while still shutting down creeps definitively and even verbally or physically violently if need be. For those of you who are familiar with MUC – Managing Unknown Contacts – it’s the same thing, but cloaked in the social expectations and grease that most of us are subject to in everyday life, especially around people we know or think we might want to know.

Creep management is an issue for far too many of us, but the skills can be learned. Besides, whether it’s being able to turn up boundary creation and enforcement more explicitly when a strange person starts walking towards us in a shadowy parking lot or being able to maintain healthy personal relationships with loved ones, being able to define, communicate, and defend the lines around you will make every aspect of your life better.