When I first started making noises about learning how to ride a motorcycle, one of the things I was told (besides learn about countersteering) was that I would find a lot of crossovers between the tools and strategies that would help me stay safe on a bike, and the tools and strategies that help me stay safe in the rest of the world. Riding and, well, life, can be risky propositions so it makes sense that there would be parallels. I found one especially useful idea in my Motorcycle Safety Foundation Basic RiderCourse this past weekend. It’s called “risk offset” and it’s a way of thinking about the activity you’re about to participate in and the skills that you have relating to that activity.

Risk offset is based on two scales: how much risk is involved in the activity, and what your relevant skill level is at the time you’re participating in it. Determining each requires both a bit of objectiveness and a judgment call.

When we think about risk, we need to consider how likely it is that something can go wrong, and how bad “wrong” can look. It’s an equation that calculates the odds and the stakes, to reference John Hearne’s statement about carrying a gun because while the likelihood of needing lethal force in self defense are low, those rare situations are a life or death proposition. Here, though, we aren’t going all the way through to that conclusion of, say, carrying a gun. Instead, we need to think about the things can happen, especially the bad ones, and then how likely they are to happen. As we go through that exercise of listing out all of the things that could happen and their probability, we also need to consider if those bad things are minor, major, or somewhere in between. We don’t, however, yet need to determine how we might influence that raw level of danger inherent in the thing we want to do. In that stew is a determination of whether and how an activity is risky or not.

Because it’s so complicated, using someone else’s analysis can be helpful here. For example, most people would say that riding a motorcycle is a high-risk activity, while sitting at home watching your favorite streaming show is generally a low-risk activity. Even if getting older means tweaking a back or a knee just getting a drink out of the fridge, and some of us are just clumsy enough that walking down the stairs can mean a sprained ankle or banged-up elbow, “normal people” perception of risk is still a useful starting point because risk levels lean more towards an objective measure, just nuanced to your particular life circumstances. As you add it all up together, remember that more risky might mean a high likelihood of many small negative outcomes, a medium likelihood of a very bad result, or a low-but-not-zero likelihood of a your worst nightmares coming soon. In the end, the idea is to figure out if something is risky, not risky, or somewhere in between.

Then, separately, you need to figure out what your relevant skills are and how good you are at them. In the motorcycling world, that means an honest assessment of how well you know how to operate the motorcycle as a mechanical matter, and how well you can perform skills like starting, speeding up, turning, swerving, and stopping. In the self defense world, it’s looking at things like how successfully you can talk your way out of a conflict, how well you can fight, how good of a shooter you are, how fast you can run. We’re not just talking about the skills that go with life-threatening situations either, but also skills like how good you are at rescuing food from bad recipes when faced with a risk of a disastrous dinner party you’ve invited your boss to. Gear plays a role, but only in so far as how closely you can interface with it and make it perform to its limit. Personal factors play a role too: how tired you are, how sick, how distracted.

It’s easy to overestimate one’s own skill in a particular arena. While imposter syndrome runs rampant and many of us feel like we are far less competent than we actually are, we also like to secretly think we’re actually pretty good at a thing and in reality, are sometimes more afraid of claiming that we’re good than of not being good enough. Which distortion of our self-perception is in play at any particular time can be difficult to figure out. That’s why here again, it can be useful to seek an honest outside, objective appraisal of our skill level. We can do this by asking a trusted expert, taking a class, and reflecting on and journaling our experiences, among other ways. Are we at a high skill level, or a low one, or somewhere in between? Getting the answer right is important, because it will tell us whether we are about to get in over our heads with an unbalanced risk offset.

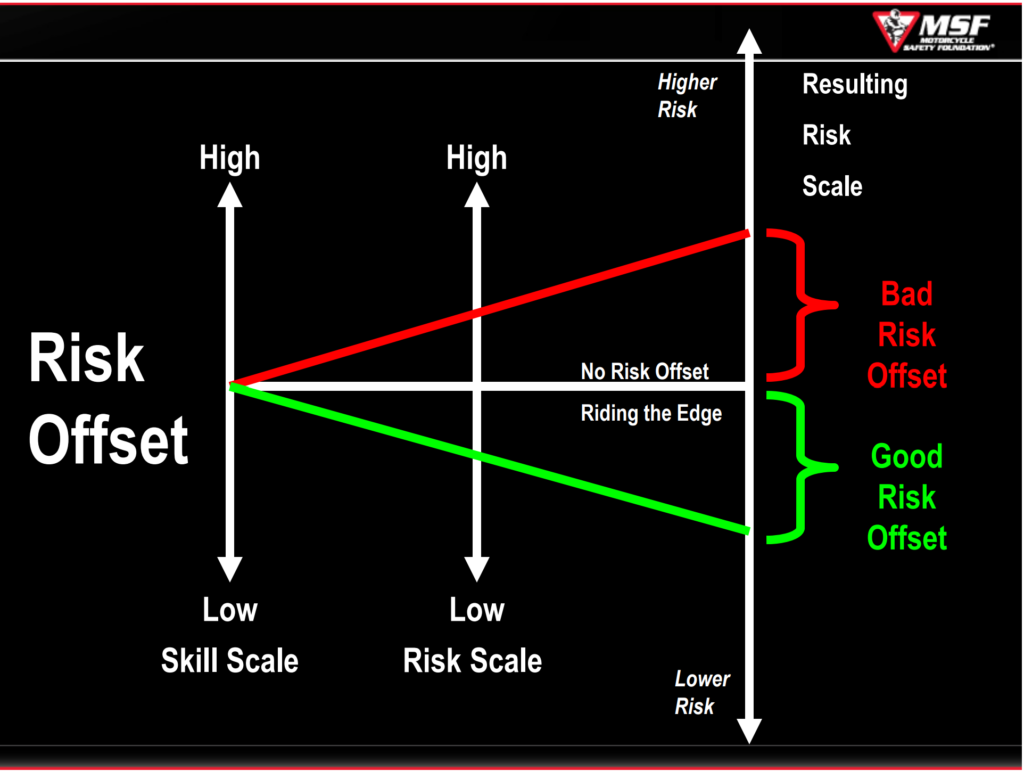

That’s because risk offset is taking those two values and balancing them against each other. The degree to which there is a mismatch between risk and skill determines the kinds of outcomes that can be predicted. If there is a very high risk and a very low level of skill, the outcomes are very likely to be negative: something bad is likely to happen, and the person involved won’t have the skills to manage it. Conversely, if there is a very low risk and a very high level of skill, the outcomes are very likely to be positive: something bad is unlikely to happen and even if it does, the person involved will easily be able to deal with it. Somewhere in between is where it gets harder to figure out if a person will be able to walk away from a risky situation unharmed. The chart here can help you visualize what that looks like, by putting each point on the scale and drawing a line between them.

Ideally, we should be working on reducing the risk of a situation, perhaps by avoiding it altogether or finding a gear- or behavior-oriented solution to make it less likely bad things will happen. In the motorcycle world, it could be as simple as slowing down well before you get to an intersection that you know people like to run red lights or stop signs through, or avoiding it altogether. At the same time, we should be increasing our relevant skills – learning how to watch for incoming vehicles, becoming masters at stopping short or speeding up quickly to avoid cars appearing where they shouldn’t be. If we can’t, then we at least need to know that our skills can’t quite match up to the risks we’re facing, and compensate accordingly: agreeing to use an escort from our school or office buildings through dark parking lots, increase our following distances to give us more time to react, choosing easier recipes…all things that reduce the level of risk so that our skills can outrun them more easily.

How safe something is or isn’t is sometimes used as a proxy for risk, but it’s really not a straight analogue. Safety is the result of figuring out the risk offset and ensuring that our skills are sufficient for the risks we face, no matter what the context. That makes whether or not a particular situation is safe an individualized assessment, that takes into account your ability to handle the dangers that might exist within it. An activity or a place being risky is only part of the analysis of whether or not you’ll be safe when you’re in the middle of it.