Much has been written and discussed about the case of a couple killed by their neighbor over a dispute apparently related to snow shoveling, with one of the more recent storms to hit northeastern Pennsylvania. If you’ve managed to miss hearing about it, the people involved reportedly had a history of not getting along, culminating in an angry confrontation, the neighbor retrieving guns, and shooting the couple multiple times. There are many lessons to learn about managing relationships with the people in our lives we can’t avoid and have to live with, the responsibilities inherent in owning firearms and having them available to us, and ways in which we might need to be able to defend ourselves. They’re all out there (though if you like, feel free to discuss in the comments!), so I want to focus on something else, something you might at first not think is really part of the issue here: situational awareness.

Lots of people in the self-defense world talk up situational awareness as a key to avoiding potential problems. If you pay enough attention to the world around you, the theory goes, then you can send warning signals to attackers that you see them coming and aren’t an easy target, sidestep aggressors entirely, or at the very least be prepared enough to take the initiative in a pending fight. In real life, it doesn’t work quite that way though. We can perceive certain things that are behind us but we certainly can’t see back there. With eyes only in front of our heads and imperfect direction-finding via our ears and noses, there’s a limit to what we can physically sense in terms of oncoming danger even assuming that we can keep up the necessary level of alertness at all times in all places. Plus, you know, bad guys often make a point of being hard to find before they start their attack. Because of that, I don’t like situational awareness touted as some of sort of panacea for personal safety.

There’s another problem with shouting “situational awareness” as a one-size-fits-all solution that this case illustrates. It’s that we can see or sense something and not know the right way to respond to it so that we can stay as safe as possible. Some of that is because we don’t know what we’re seeing. Some of it is because we see it and we don’t believe it or its implications.

Violence doesn’t necessarily look like it does in the movies or on TV. We know this intellectually, but that doesn’t mean we can spot it when it’s in front of our faces. Training helps, along with watching surveillance, security camera, and badge cam footage. But it’s not quite the same when it happens for real. For instance, even if you are familiar with the sound of gun fire from going to the range, hearing it in a suburban neighborhood is completely different. The echos aren’t the same, the sound travels differently, and the setting isn’t “right” for you to always accurately identify it versus making excuses for it being something else. That doesn’t mean you’re a failure or even that you need to train more. It means you live a fairly average life, as broad American statistics go. Similarly, you might not know what it looks or even feels like “for real” when someone, even you, gets shot or punched. It may look less bloody than you expect, or more. It may hurt more than you thought it would, or less. There are lots of reasons for that, not the least of which is that it’s impossible (and really, not advised) to get first-hand experience with all of the possibilities that you could run across. The kinds of violent events we prepare ourselves against tend to be outliers in the first place, and all of the variables can be extraordinarily difficult to map out.

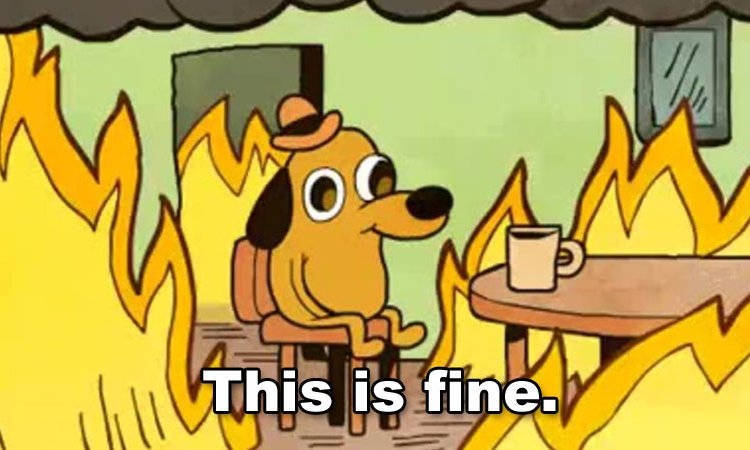

Then again, you might see it and you might know what it is, but you don’t really SEE it. Maybe you’re tired or busy or stressed out and just not really processing what’s happening. You could be alert enough to spot it all, but the warning bells that should sound don’t ring or you hit snooze and move on. Often, there are no consequences for failing to spot or ignoring a red flag, so we aren’t really conditioned to watch for them more carefully when we come across them again. That’s not a bad thing; it means we live relatively safe lives. The problem comes when the flag is lit up in flashing neon lights and we still make excuses that everything is going to be just fine. That’s exactly what happened in this snowy shooting. It’s true that when you see someone yelling at you in anger, it doesn’t mean you know if they might try to assault you. You might have had that fight with them before and it simply ended in nasty words and huffing and stamping away. It’s also true that violence usually comes with warning signs. If someone says they’re going to shoot you, this might be the time it’s true. This couple found out the tough way that angry yelling, and even a gun being waved around, really were red flags warning of real danger.

So yeah, situational awareness. It only helps you if you can identify what you’re sensing and then act appropriately on that information. Since what you can see, hear, smell, and even taste are imperfect and your knowledge will have gaps, and because we are human and default to assuming that everything is going to be okay, that makes relying on situational awareness as the one magic tool for personal safety an unsure bet.